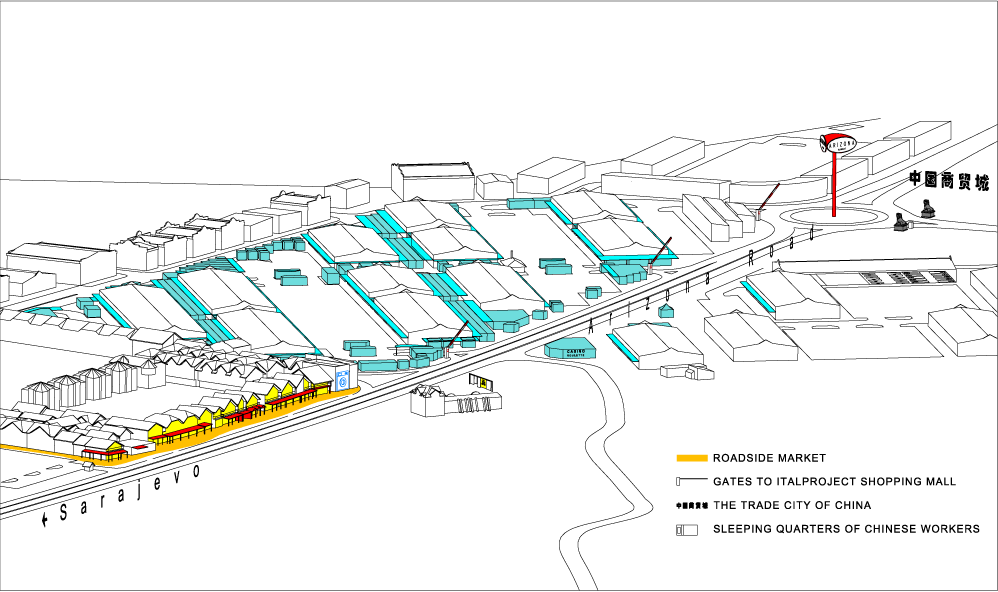

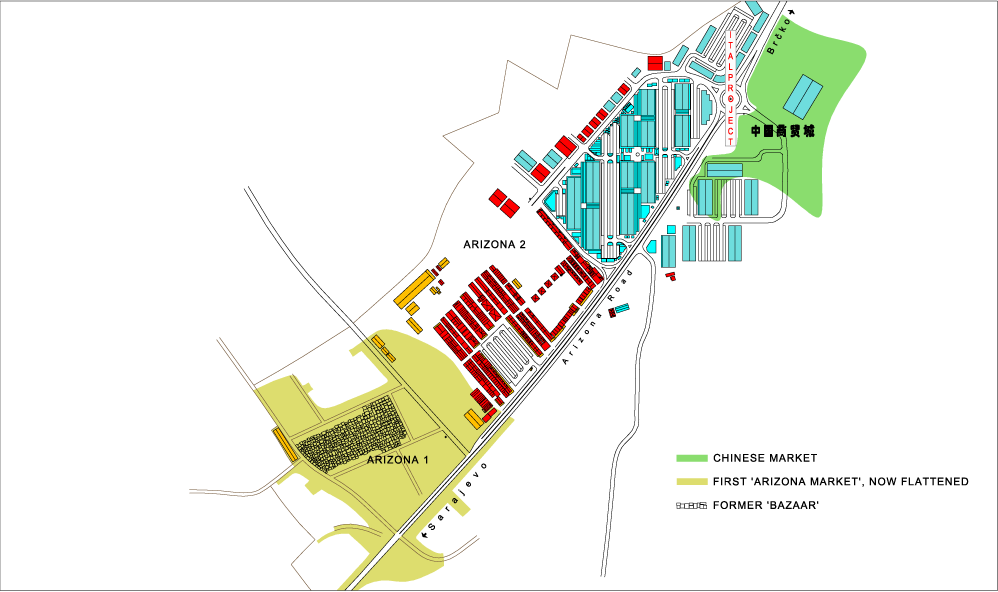

‘Arizona Road’ in 2001

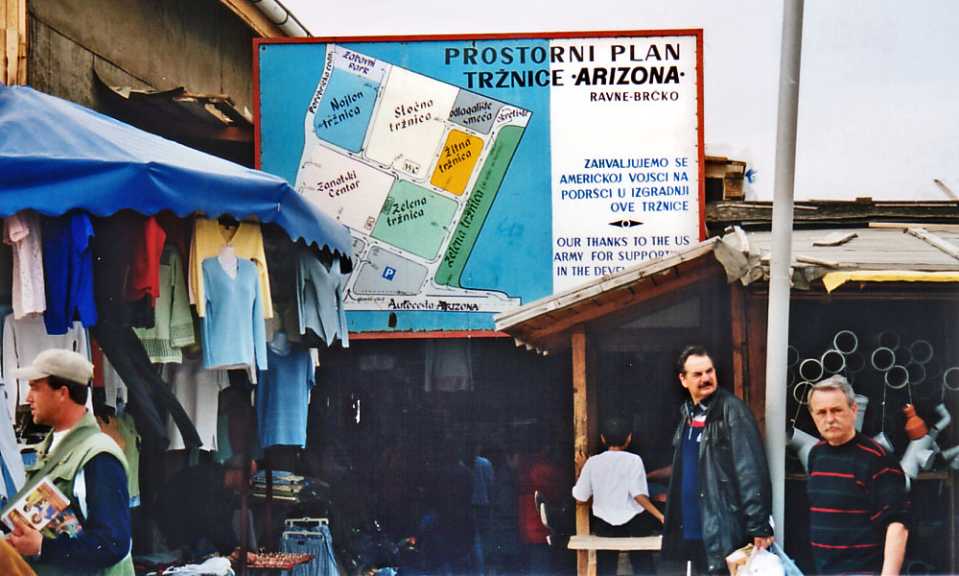

Entry to the market via metered parking lots

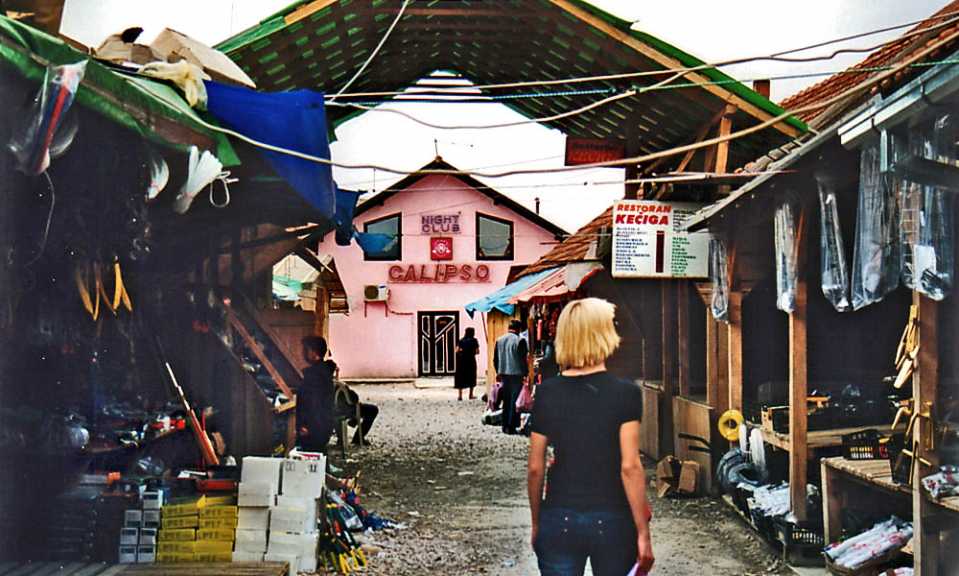

Entrance to bazaar-like heart of the market in 2001

Warehouse structures erected by Italproject now housing the new indoor markets

One of the nightclubs at Arizona Market in 2001

Less frequented warehouses partly used as sleeping quarters for Asian workers

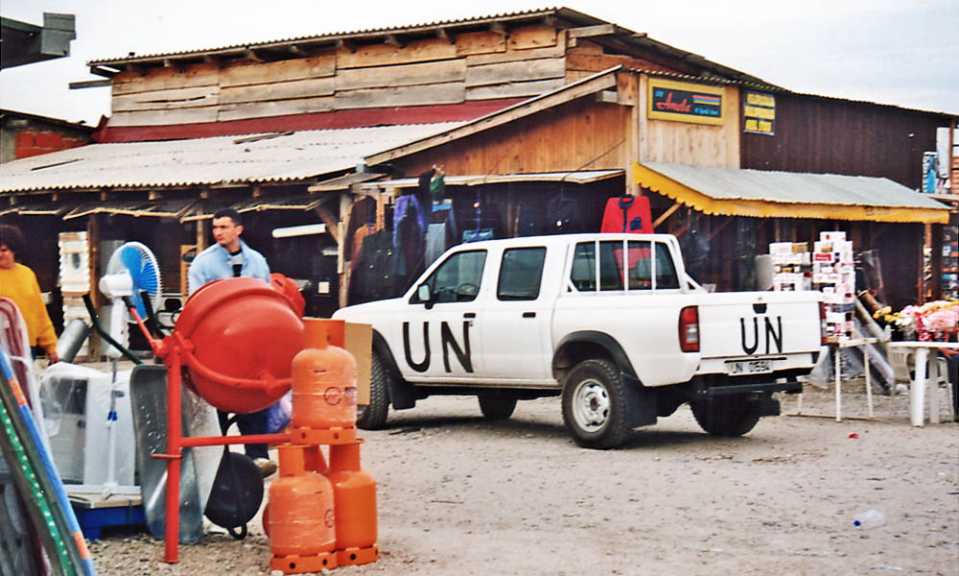

A UN vehicle at the market in 2001

Commercial development where building the facade is part of the individual fit-out

Members of the International Community browsing magazines in 2001

Italproject offered existing traders the opportunity to rent or buy stalls in module-like rooms. Resistance by landowners and traders to this total takeover was met with compulsory dispossessions. This response was justified with the argument that it was in the public interest to ensure that the district administration of Brčko complied with the agreements concluded with Italproject (3). Demonstrations and road blockades staged to oppose the demolition of the old site were cleared by the police. As most of the landowners affected were Croatians who sought the support of nationalist groups to assert their cause, the maxim of achieving reconciliation by taking economic measures came dangerously close to fomenting an ethnic conflict as a result of what was seen as an arbitrary allocation of economic options.

One of the most striking things about this strategy to regain control over Arizona Market – which ultimately culminated in the ceremonial opening of a new shopping centre in the presence of the Principal Deputy High Representative, the US Ambassador, Donald S. Hays, on 11 November 2004 (4) – was the way the international community, which exercised politico-territorial control, and an international investor co-operated in privatising the public domain of the market. The transformation of the informal market into a shopping centre signalled a critical turning point, revealing the limits of translating between formal and informal systems. The ‘spontaneous’ evolution of a public-urban space in the shape of an informal market surrounded by transporters and huts was replaced by enclosed fee-charging parking spaces. The coming together of diverse cultures was now regulated by fixed opening hours and private security guards.

In only ten years, Arizona Market has been transformed from a space of bare survival into a centre of ubiquitous consumption. What was once a mere border guard post has now become a post-metropolitan territory. Hopes that Arizona Market might become a model for a self-organised town were dashed when a market arose whose existence and development were far more extensively tied up with the presence of the international defence force than that formerly generous gesture to bulldoze a few fields seemed to suggest. The UNHCHR attributes the crisis – the dramatic increase in prostitution and trafficking in women – to, among other things, the presence of over 30,000 peacekeepers in BiH (5). Bosnia was not so much a transit country as a destination for women victims of trafficking. The SFOR troops were not only customers, but allegedly also had their share of the profits accruing from smuggling and corruption. The ‘solution’, based on the model of ‘urban renewal’ developed in the USA in the 1960s (declaring a district a problem area and thus permitting large-scale expropriation in the name of the ‘public interest’), was fostered by the transformation of the legal system in the Brčko district with the help of legal advisers financed by USAID (US Agency for International Development) (6).

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...