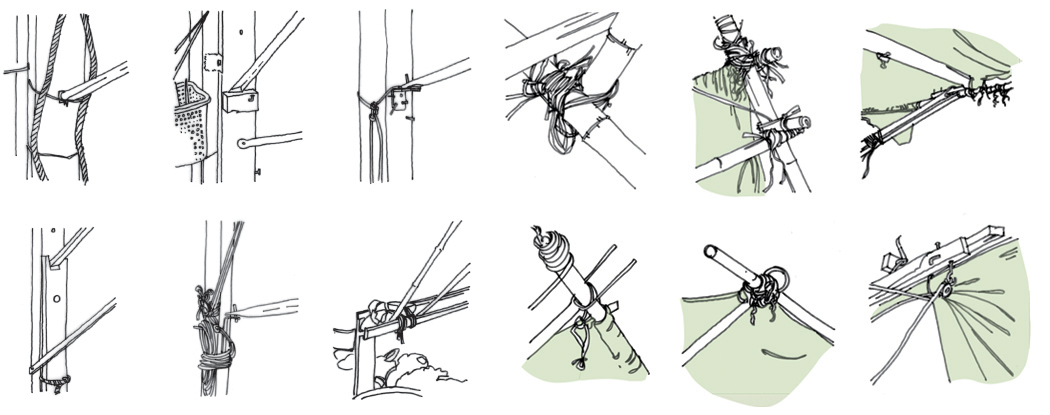

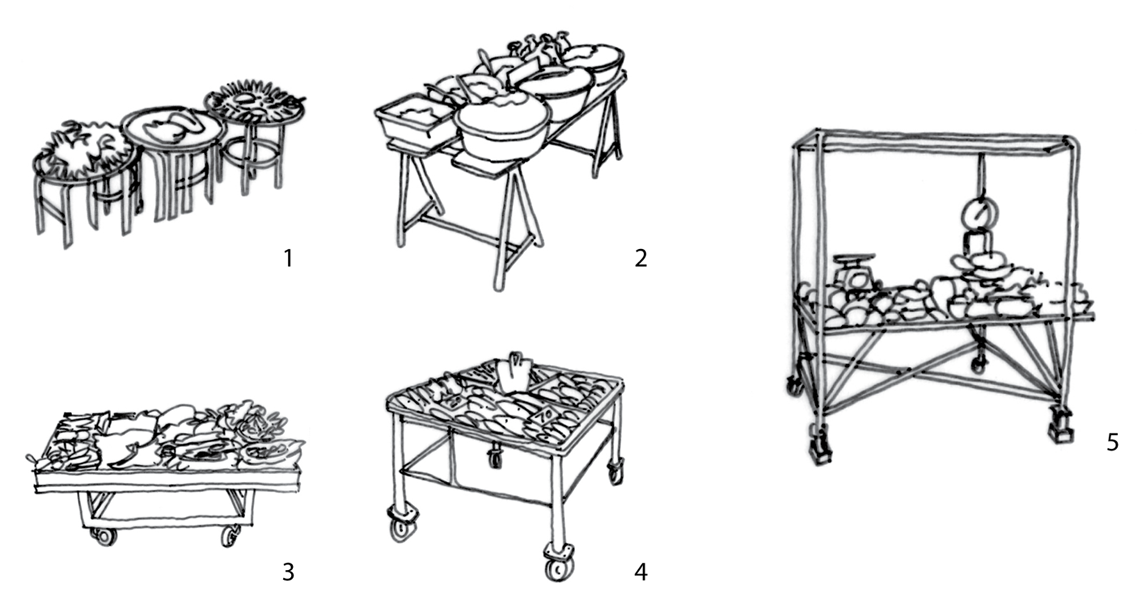

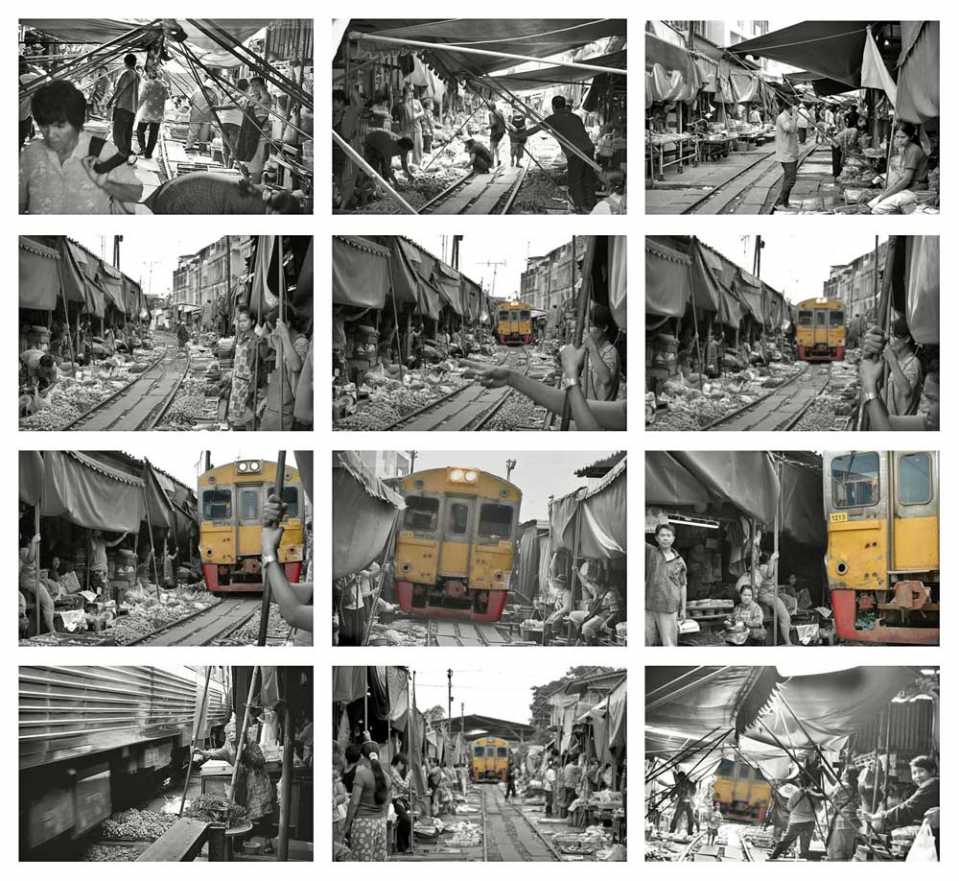

Though architecture has normally locked itself into patterns of thinking which are inscribed into its ideology and its codes, Rom-Hoob market, as completely intuitive and easy to construct, stands in stark contrast. Its construction can be performed by people without substantial prior knowledge and makes use of existing and easily found materials (2). One might conceive of architecture as something artificial, distinct from the natural. One might view architects as separated from ordinary people by their profession as the agents and providers of architecture. Rom-Hoob market, though, suggests these assumptions need reexamination (3). Rom-Hoob market illustrates that people here are, to a large degree, acting as architects. They exist in a dynamic relationship with the local environment and construct their shelters in creative ways that retain a sense of local ownership by subverting local materials for novel purposes. They are all continually involved in co-constructing places for themselves, and enact a complex range of relationships between them and their space in order to do so. They generate subtle and complex patterns of conceptual structure, instinctually taking into account relationships and geometries. In this organic self-directed enterprise, we see that the language of architecture, at least at its fundamental level, is shared by all (4). This represents a shift from the perfect Euclidian geometries to a colloquial architecture which contains a certain kind of appreciation for space, thereby yielding a different kind of spatial experience to users as well as a distinct interaction with the flows.

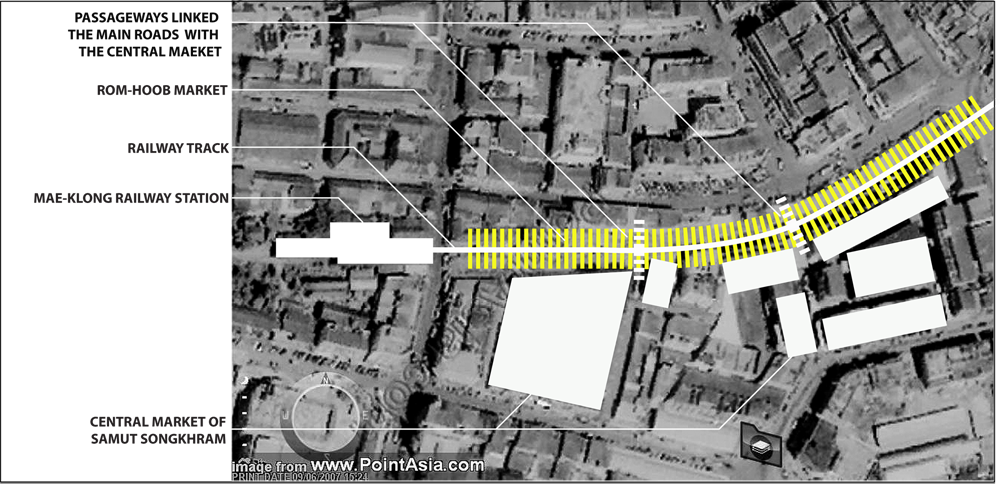

By looking at the urban context of Rom-Hoob market, we see that it is not only shaped by the movement of trains and users, but in fact by the flows of capital and economics themselves. The form of the market is squeezed and stretched along the railway track because of the space limited within the city which is in turn affected by the flows and growth of the capital. Moreover, the utilized spaces within the market are similarly defined by the particular flows of transportations and goods. The language of this colloquial architecture which emerges within this context is then constructed by the everyday lives and needs of the community; and in particular the energy of flows. This suggests that the existence of Rom-Hoob Market (excludes street markets) disprove Castells’ historical claim, namely that flows displace spaces of places. Today’s architecture seems to survive only when it reflects what the society or culture expects of it and particularly when our society and (architectural) culture rely on the flows. But Rom-Hoob Market offers a way in which places are perceived and appropriated across the internal space of time and culture. This suggests that it may not be necessary to search for emergent possibilities in constructing architecture in our fluid world. Perhaps by looking back to the local and the everyday discourses, an idea or alternative conception of what architecture in the space of flows can be will emerge.

Soranart Sinuraibhan

Faculty of Architecture

Khon Kaen University

Thailand

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berleant, Arnold. “The Aesthetic in Place.” in Constructing Place: Mind and Matter, edited by Sarah Menin, 41-54. London and New York: Routledge, 2003.

Castells, Manuel. The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

Kahn, Andrea, and Carol J. Burns, eds. Site Matters: Design Concepts, Histories, and Strategies. New York and Oxon: Routledge, 2005.

Lefebvre, Henri. Everyday life in the modern world. New York: Harper, 1971.

Wigglesworth, Sarah, and Jeremy Till. “Table Manner.” Architectural Design 68, no. 7 (July 1998): 31-35.

Unwin, Simon. “Constructing Place on the Beach.” in Constructing Place: Mind and Matter, edited by Sarah Menin, 77-86. London and New York: Routledge, 2003.

(1) Interviewed with locals at Rom-Hoob Market (January 12, 2007)

(2) Sarah Wigglesworth and Jeremy Till, “Table Manner,” in Architectural Design 68, no. 7, (July 1998): 31-35.

(3) Read more on “Beach Architecture” in Simon Unwin, “Constructing Place on the Beach,” in Constructing Place: Mind and Matter, ed. Sarah Menin, (London and New York: Routledge, 2003).

(4) Ibid.

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...

read more...